It has been eight months since we concluded our Mediterranean Cruise in Fusina, the Venice cruise port on the mainland, and it is high time I assembled a report about our post-cruise stay in Venice. But before we get lost in Venetian details, I want to make a statement, a declaration you might say:

Venice. There is no other city like it.

The Venice we experience today is a slightly tired grand old dramatic actress, burdened by her fascinating history which is as much a memory as it is part of everyday life. Building an offshore community in the Venetian lagoon encouraged the development of a culture with its own language and traditions that has a distinct rhythm of life at one with the tides. Daily life in Venice isn’t significantly different now, than it was during the heyday of the Republic as a maritime powerhouse, just the plumbing works better and the boats are faster and louder. The sea lent the Venetian people the power to weave a spectacular fabric of global commerce and outstanding art within the confines of a small city-state that still has an undeniably unique atmosphere. But the power is shifting back to the sea, and proud, beautiful Venice appears frail.

With the help of Wikipedia, I can tell you that Serenìsima Repùblega de Venèsia or, as we would say in English, the Most Serene Republic of Venice, La Serenissima, was a thalassocracy consisting of the City of Venice plus possessions in Slovenia, Croatia, Montenegro, Greece, Albania, and even Cyprus. For one thousand and one hundred years, Venice was a sovereign state, rising from a salt trading group of small Adriatic coastal islands to a powerful republic, constantly wrangling over territories with the mighty Ottoman and Habsburgian Empires.

We had booked a post-cruise boat tour to pass some of the time between being kicked off the cruise ship before breakfast and an afternoon AirBnB check-in, while simultaneously getting to know the lay of the land, so to speak, because this was our first visit in Venice. The tour was basically a sound idea, but heavy rain and cold winds made a Venetian canal excursion lasting several hours only marginally enjoyable, despite the mostly enclosed seating on the lower boat deck.

It was a guided tour and our guide, a Catalan lady married to a Venetian, was doing her best to impart Venice’s secrets to us. There were only six former cruisers who had elected to buy into this wet and draughty enterprise on a boat that could easily accommodate 60. As it turned out, it was not only difficult to see the passing scenery of Venetian landmarks, it was equally challenging to understand the guide’s remarks about them. Engine noises, heavy rain pounding against windows and decking, and choppy waves drumming rhythmically against the metal hull of our vessel reduced her voice to a charming murmur of rolling Rs in synch with the rolling seas. She couldn’t utilise the boat’s audio system to make herself better understood, because it only had speakers on the uncovered upper deck.

My husband did the only sensible thing. He found a nearly comfortable corner on one of the build-in wooden benches and slept through most of the tour. I, on the other hand, was wide awake – possible owing to the three espressi I had gulped in short succession to find some warmth. Although mostly in blurry images, I nevertheless did see large parts of the archipelago of Venice with its multitude of islands of all sizes with monasteries, cemeteries, and ancient and more contemporary neighbourhoods. As la doña Catalana revealed, there was a whole lot more to discover about Venice than Saint Mark’s Square and the Rialto Bridge!

Around noon, our fairly bizarre tour concluded back at the former cruise terminal on Venice island whence it had started, and we found the terminal complex entirely deserted. Without the assistance of our tour guide, we would have been stranded there in the pouring rain, searching far and wide for our bags and onward transportation. She called around and raised a couple of guys with keys to the luggage storage. Then she called around some more to find a water taxi for us, since the taxi booth was also firmly shuttered. As a final act of kindness, she walked with us to locate the proper pier for the taxi pick-up. Sadly, I’ve since forgotten her name, but this lady from Barcelona was one heck of a precious gem.

Our Venetian rental apartment was located in the sestiere or district of Cannaregio in the northern quadrant of the Island of Venice. Since the building wasn’t directly at a canal, but down an ally halfway between two canals, I gave the water taxi driver the name of a hotel at the canal to the north of our apartment.

As is customary in Venice, the hotel had a backdoor and steps leading down to the canal with a platform to receive guests arriving in water taxis. Our driver rang the bell and banged on the door, but nobody showed up. We were, after all, not expected.

The canal cabby then reversed his shiny, teakwood boat, until he came alongside the bank of the rio to the left of the bridge. There were no cleats or rings to belay the boat, nor were there any steps. He somehow managed to keep his taxi more are less in place, while flinging our heavy cases onto the cobbled lane and assisting with our clumsy disembarkation manoeuvres. How I got up there, I erased from my memory. From there, it was just a few steps to our gate. The apartment still wasn’t ready, but we could leave our bags to explore the area for a place to eat. The gnocchi in the nearest Osteria were more than welcome after a long morning without any breakfast.

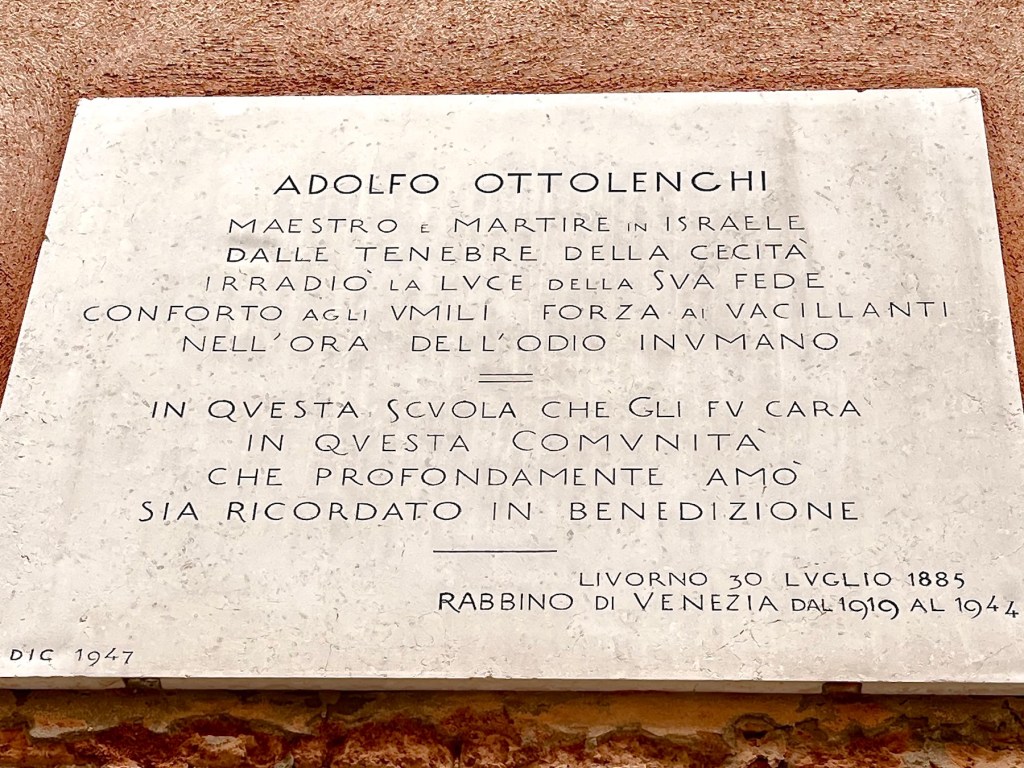

The Venetian Ghetto is also located in the Cannaregio district, and we just kind of drifted there after lunch despite the intermittent rain.

The Ghetto held a number of surprises for us, as we discovered more and more of its history.

The Doge Leonardo Loredan, with the full support of the Senators of the Republic of Venice enacted a decree on March 29, 1516, that restricted all Jews, residents and visitors alike, to live and work in a shabby area of copper foundries. The Venetians called this neighbourhood gèto [jeto], a word that mimics the hissing sound of jets of molten metal hitting moulds in the foundries. When Ashkenazim from Central Europe arrived in Venice, their guttural pronunciation turned the soft gèto into a hard gheto and the term ghetto was born.

The segregation and forceful confinement of Venetian Jews for the protection of Christian souls continued for 281 years, until May 12, 1797, when the last Doge Ludovico Manin abdicated and the Republic of Venice ended at the hands of a 28-year-old French general from Corsica, called Napoleone di Buonaparte. He had the gates to the ghetto removed once and for all on July 11 of the same year, declaring Venetian Jews to be equal to Christians.

The Ghetto di Venezia is considered to be the oldest ghetto in Europe. As far as the name goes, that is certainly true since the very word ‘ghetto’ was coined in Venice. It is however not the oldest documented enforced segregation of Jews by Christians. Not taking outright evictions or pogroms into consideration, that dubious honour goes to Frankfurt am Main, Germany, where Holy Roman Emperor Frederick III decreed in 1462 that a lane just outside the city wall was the only place where Jews were allowed to live and work. The ground itself, mind you, still belonged to proper citizens, but Jews could build their houses there. At their own expense, naturally, while paying property taxes to owners and also the city. The lane was called Judengasse, lane for Jews, as the word ghetto not yet existed. In 1811 the Jews of the Judengasse of Frankfurt were emancipated by order of a certain l’empereur Napoléon 1er, who, even at the height of his power had not forgotten all of the principles of the French Revolution.

The gates to the Venetian ghetto were locked at night, and the canals surrounding it were patrolled by boat, at the expense of the residents, who were severely punished for breaking curfew. Jewish men had to wear yellow hats, except for medical doctors, who were allowed to wear black hats like Christian men did. Practicing medicine was one of the few permitted occupations. Ragmen could sell used merchandise and run pawnshops, like the Banco Rosso in the Ghetto Nuovo. During certain periods, ghetto money lenders were granted a special license to make loans to Christians under stiff tax obligations, always with an eye on a potential profit for the Republic.

In general, the Serenissima Signoria, the governing body of the Republic of Venice, was more pragmatic in her approach to foreign merchants than either Catholic or Protestant rulers throughout the Holy Roman Empire and beyond. Making money was the overriding principal in Venice, so they tolerated not only Jewish, but even Turkish merchants, not withstanding that the Ottoman Empire was their eternal archenemy.

One remarkable fact concerning the Venetian Jewry, was their high level of learnedness, both in Rabbinical and in secular subjects. One such outstanding scholar was the amazing and multifaceted Rabbi Leon Modena (1571 – 1648). Modena was also a driving force behind the thriving printing industry for Hebraïc literature. One-third of the roughly 4000 volumes printed in Hebrew by the mid-seventeenth century, were printed in the Ghetto.

A couple of contemporary artists continue the printing tradition of the Ghetto di Venezia, as we discovered when we stumbled into the gallery and shop of Allon Baker and Michal Meron in the Ghetto Vecchio. Michal is well known for her illustrated sidrot or weekly Torah portions, and also for her Venetian scenes which she paints in a charming naive style, while Allon, an abstract painter, self-publishes a Passover Haggadah with original material from 1609.

We were surprised to find out that the inhabitants of the Ghetto di Venezia never assimilated into a coherent Jewish community, but remained true to the religious practices, traditions, and languages of their regions of origin. Each group built their own synagogue called scuola, school, after the Yiddish ‘shul’, place of learning. These distinct regional entities were ranked according to the respective wealth of their community members. Sephardim from Portugal and Spain occupied the highest rung, followed by Levantine Sephardim. Below them ranked Germanic Ashkenazim, while the homeboys, the Italians, were the poorest inhabitants of the ghetto.

Central European Ashkenazim were the most numerous ghetto residents until the expulsion of Jews from the Iberian peninsula toward the close of the 15th century. That migration eventually brought a large number of wealthy Sephardic merchants to Venice. As latecomers, their synagogues were “clandestine”, they weren’t allowed to be identified as houses of worship on the outside. But they were opulent inside, and the rich merchant community commissioned the most prominent Venetian baroque architect of the 17th century, Baldassare Longhena, and the sculptor Andrea Brustolon to restore and enhance their sanctuaries. Their poor sister, the Scuola Italiana was equally obliged to be clandestine, but rather plain on the inside as well. The sanctuary had only room for 25 members who followed the ancient liturgical Italkim rites that go back to jewish communities in ancient Rome.

A marvellous discovery in the Venetian ghetto was the unexpectedly joyous atmosphere we encountered throughout – once the incessant rain stopped. Such zest for life! A gaggle of Yeshivah students bursting through a restaurant door, laughing and calling out to friends, epitomised an easy, contemporary Jewish environment within the traditional quarters of their ancestors. I do have to emphasise, however, that the Ghetto di Venezia per se is simply a tourist attraction, very few families still live there – a situation that mirrors Venice at large. But there is an active Chabad synagogue, an oven for unleavened bread, a Yeshiva, ‘Gam Gam’ the kosher restaurant, and so forth, all run by the local Ludavitchers.

More impressions from our meanderings through Cannaregio,

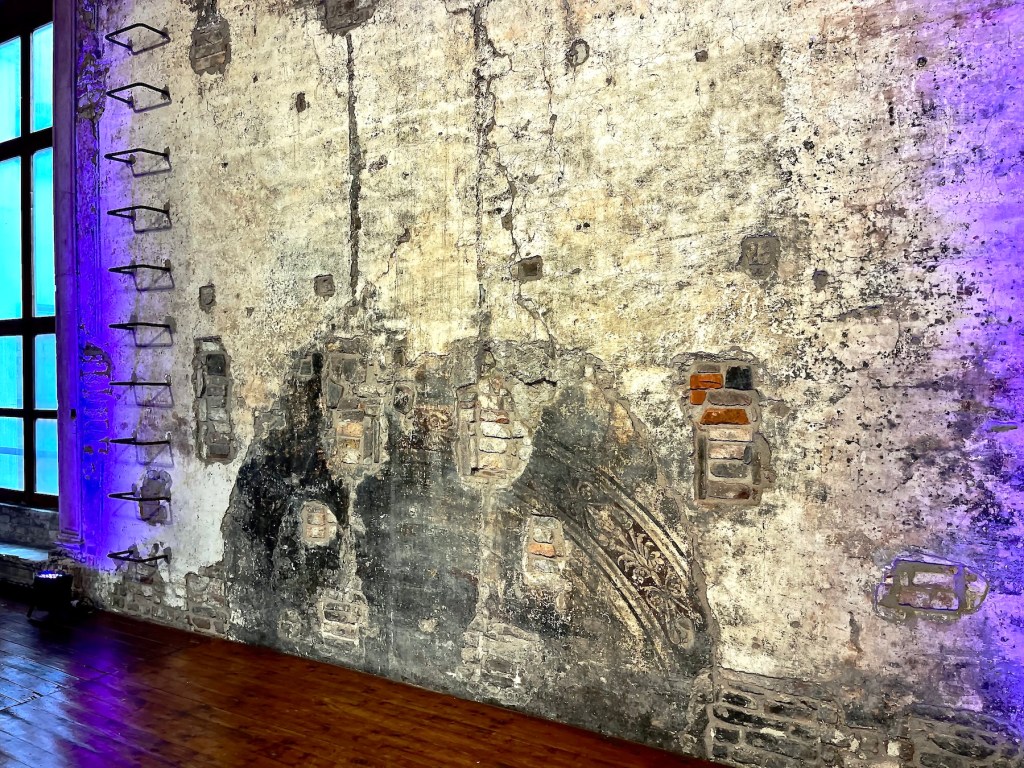

This is my favourite picture of Venice – sad, magical, broken, charming, worn, dreaming of its past glory. These days, most young families prefer to raise their children on the mainland, leaving the old and feeble behind, who live in the shadows, just out of sight of the boisterous tourist crowds. The cost of living in Venice is enormous, yet the taxes charged are never enough to maintain the ancient infrastructure, especially under the added pressures of climate change.

The Venetian dwellings were built by driving wooden stakes into coastal mud. Mud isn’t very stable and tidal flow doesn’t help. Venice essentially started sinking while it was being build. Diverting rivers away from the lagoon and draining groundwater for use in factories on the mainland increased the inherent instability of island Venice. It seems miraculous that there still is a Venice, as it now has to overcome two strikes against it, which ironically reenforce each other: unstoppable sinking and rising water levels.

In November of 1966, a huge flood nearly drowned the city once and for all. This catastrophic event was an alarm bell the Venetians heard loud and clear. Plans for an innovative system of protective flood gates were drawn up and partially implemented within twenty-five year. Not even the Dutch, recognised masters of tidal control, had ever thought of a system like MOSE. The acronym stands for MOdulo Sperimentale Elettromeccanico meaning experimental electromechanical module, although its other meaning, Moses [Mosè in Italian] is distinctly apropos, and a heck of a lot more romantic. Mose consists of permanently submerged devices that can be raised temporarily to block high tides entering the lagoon. You can find fascinating details on the hugely expensive and controversial, but effective Mose system in these articles:

engineering.com and curbed.com

Without realising it, we had actually passed the bright yellow Mose Control Center during our initial rainy Venetian boat tour and then we saw it again during vaporetto rides. Mose is housed adjacent to the huge Arsenale di Venezia, the famous 12th century maritime shipyard of the Republic of Venice.

One day we took a vaporetto to the Arsenal in the hope of seeing some of its historic buildings, and/or art installations from the last Venice Biennale – the 60th edition of which will open in April 2024. Unfortunately we didn’t do any advance preparation, just going on a whim, and as a result we saw nothing of note and the largely deserted area felt rather creepy.

After a last look toward the Arsenal, we explored some off the beaten path areas in the sestiere Castello, before stopping for lunch.

Back in Cannaregio, our favourite sestiere!

One can not be in Venice without going to the island of Murano. So we moseyed on over to our bus stop to take a vaporetto to Murano, a roughly 20 minute ride.

We walked along what appeared to be the main drag, enjoying some window shopping. The range of glass objects on offer was quite amazing. Especially enticing were large objects d’art displayed in elegant galleries for enormous asking prices.

Our arrival-day tour guide had told us that glass blowing was a dying art and many glass blowing workshops had shut down, because the maintenance and running of a fornace, the traditional kiln, was too expensive and a significant source of pollution. She did recommend to visit the Glass Cathedral – Santa Chiara, thought, where we could get an idea of the ancient craft by watching a glass master at work.

The Glass Cathedral turned out to be a family enterprise headed by one Giovanni Belluardo, offering a near continuous glass blowing show in a wide range of languages, either with or without Prosecco. In 2012 the Belluardos purchased the former Chiesa di Santa Chiara that lay in ruin. It took the family four years to rebuild the church using as much of the original materials as was possible. In addition to glass blowing demonstrations, they offer traditional chandeliers, mirrors, art pieces, and smaller souvenirs for sale. The cathedral is also used as a spectacular events venue, and the family hosts one of the famous Venetian Carnival balls.

A Glass Master at work:

Before Peter could came home, we met with Don Giovanni …

At long last, we went to see Piazza San Marco, and on a separate occasion also the Rialto bridge, taking vaporetti to enjoy the scenery on route. It was immediately obvious when our vaporetto turned from a side canal into the Canale Grande. Not only was the canal itself substantially wider and busier, but the houses framing the waterway were distinctly posher, one palazzo chasing the next. However, their grandeur notwithstanding, quite a few appeared to be in poor repair. The upkeep of a centuries-old building in our increasingly extreme weather situation is becoming prohibitively expensive for more and more owners. The best maintained palazzi were usually either luxury hotels, or belonged to foundations.

Another interesting aspect of sightseeing along the Grand Canal were churches with huge advertisement displays that looked rather incongruous in juxtaposition with sacred cupolas. It appeared that the rental income from the ad space is used for restoration work on the buildings.

A Barbarigo family legend states that in 880 CE their ancestor Arrigo won in battle against Saracen pirates. He cut off their, no, not heads, but their beards, barba in Italian, and brought them home as prove of his accomplishment, hence the family name.

Eventually, a glass manufacturer bought the 16th century Palazzo Barbarigo, and in 1886 he decorated the front toward the canal with Murano glass mosaics. Their neighbours, descendants of old Venetian nobility like the Barbarigos had been, considered the new façade garish and dismissed the owners as nouveaux riches.

According to Alexei Navalny’s Anti-Corruption Foundation, the Palazzo Barbarigo currently belongs to the pro-Putin Russian conductor Valery Gergiev. It was bequeathed to him by the late harpist Yoko Nagae Ceschina, who herself had inherited multiple properties in Vence from her husband Renzo Ceschina.

First up on the right, we have the Palazzo Dario, which was remodelled with extensive marble cladding and ornamentation for one Giovanni Dario, merchant and diplomat. His daughter Marietta inherited the ancestral home in 1494. She was conveniently married to the owner of the neighbouring palace, a member of the noble Barbaro family.

Ca’ Dario with its distinctive oculi, was the object of a painting by Claude Monet during his stay in Venice in 1908. The painting is now housed in the Art Institute Chicago. The residence is considered haunted by some, who have compiled long lists of former owners who were felled by misfortune or their own hand. The alleged curse is supposed to go back to a Templar burial ground beneath the structure. Be that as it may, there is definitely subsidence since the building lists noticeably to the right.

In the early 1880s, the neighbouring Palazzo Barbaro was bought by a certain Alexander Nikolaevich Wolkoff-Mouromtzoff (1844-1928), a Russian botanist and painter, who signed his work A.N. Roussoff. He is said to have painted pastels in competition with visiting artist Whistler. Wolkoff was a very good friend of Eleonora Duse, whom he hosted in his Palazzo Barbaro Wolkoff during most of 1894.

To the left of La Duse’s apartment, we find the much shorter Palazzo Salviati, home of the highly regarded Salviati Glass Company. It is a relatively new addition to the canal front, the showroom was only built 1903-06. In 1924 an extra floor was added and the façade was decorated with Murano glass mosaics in pure Art Nouveau style.

We could go on, as there is no shortage of palazzi in La Serenissima, but we were approaching our San Marco bus stop.

The 12m high marble columns were placed in the 11th or 12th century as spiritual guardians visible from the sea. Their origin isn’t quite clear, they may have been a present from Constantinople rulers, nor is it known with any certainty if a third column was indeed accidentally dropped in the lagoon, as persistent rumours indicate. The mystery extends to the statues that were later installed on top of the columns. The figure of the martyr San Teodoro was once a statue representing the Emperor Constantine, at least certain parts of it, and the slain dragon on which he stands is most likely a crocodile. The lion statue representing Saint Mark the Evangelist isn’t faring any better. It is believed to have started life as an Assyrian sculpture, possibly of Nirgal, God of the hunt. And quite oddly, it shows the winged lion with both front paws firmly placed on a book that lies flat on the ground. In the picture below, as well as in the upper segment of the clock tower further on, one can see the true representation of the famous winged Lion of Venice aka Saint Mark the Evangelist with one paw steadying an upright gospel.

We left the piazza through that large arch under the Renaissance clock tower to escape the crowds, and roamed the back lanes of the sestiere San Marco for quite a while,

finally reentering the piazza at its far end, which gave us a great perspective over the fantastic Basilica di Venezia,

and a bit of the Doge’s Palace as well.

On another day, we traveled along the Canale Grande again in our approach to the Rialto bridge.

According to the travel blog Touropia, the Rialto Bridge is #6 on their list of the 15 most famous bridges in the world. This popularity shows in the sheer number of tourists cheek to jowl on the bridge, even in early May. I would not want to be here during the high season!

The Rialto bridge is the oldest of the four bridges crossing the Grand Canal. It connects the San Marco and San Polo sestieri at the narrowest point of the canal. Earlier versions of the Rialto bridge, when it was still called Ponte della Moneta, went from pontoon style to fixed wooden structures, eventually including vendor’s stalls perched along its edges. After 300+ years of the bridge repeatedly either burning or collapsing, for example under the weight of rubbernecking crowds hoping to catch a glimpse of the bridal couple at the wedding of the Marquis of Ferrara in 1444, a first suggestion of a stone bridge was brought forth. It still took nearly another hundred years before the new, single-arch stone bridge finally became operational in 1591. It was built by architect and engineer Antonio da Ponte (1512-1597). However, rumours wafting around the new bridge, its construction and design would not cease. Many a famous architect’s name swirled about, even including Michelangelo, but a certain contemporary of da Ponte was the most likely candidate. Vincenzo Scamozzi (1548-1616) architect and respected writer on architectural theories, best known as the heir to famous Andrea Pietro della Gondola aka Andrea Palladio (1508-1580) who is considered one of the most influential individuals in the history of architecture. Both Vincenzo and Antonio submitted entries to the Signoria, when a new competition for a bridge design was called in 1587. But who won? Oh, the suspense!

In 1841 a Parisian architect named Antoine Rondelet, published a “Historical Essay on the Rialto Bridge in Venice” – only in Italian, as far as I could find. In his essay, he detailed his research regarding the building of the bridge. With the invaluable assistance of Google, I took the trouble to translate the darn thing to achieve some clarity.

Monsieur Rondelet came to the Solomonic conclusion that both architects won. Antonio da Porte, the engineer, accomplished the brilliant achievement of actually building the stone bridge by following the expert design of Vincenzo Scamozzi, the widely travelled architectural theorist, whose amazing travel sketchbook was only discovered in 1959!

“… così è tolta ogni confusione; al da Ponte l’onore dell’esecuzione, allo Scamozzi quella d’averne concepito l’idea”.

As an aside, I read in different sources that it took 12 000 wooden posts to anchor the bridge in the mud … 12 000!

Further more, I also read that Scamozzi allegedly predicted the single-arch construction of da Ponte would surely collapse … 🤔 So far it’s still going strong!

Let’s move on!

Past the Rialto bridge, we explored the vast Rialto Market area, where locals have bought their produce and fresh fish for a thousand odd years.

Lunch break near the market:

And yes, there are dragon boat races in Venice! With this picture of boat Nº3 of the local Cannaregio Dragon Boat Club, I bid you a good night.

P.S. To facilitate our departure to the airport by water taxi, I asked at the front desk of the Hotel Eurostars if we could use their water taxi stop at rio di San Alvise as an address for our taxi reservation, as well as our actual pick-up point. Luckily, they did not only allowed us to use their facilities, they even made the reservation for us! Thank you, Hotel Eurostars Residenza Cannaregio, Venezia, Italia❣️ You made our departure from Venice so much easier!!!