It’s a seven-minute drive from our vacation place to the commercial area of Pojoaque Pueblo, where we shop at the supermarket and pop in at the El Parasol family restaurant for tacos. There’s also a weekly market where locals sell their home-made products, everything from jams to fresh produce to crocheted beanies to beadwork items. My brief missive today focuses on the Poeh Cultural Center of Pojoaque Pueblo in the same location, specifically the unique, long-term exhibit of ancient Tewa Pueblo pottery at the center. The installation is called

Di Wae Powa – They Came Back

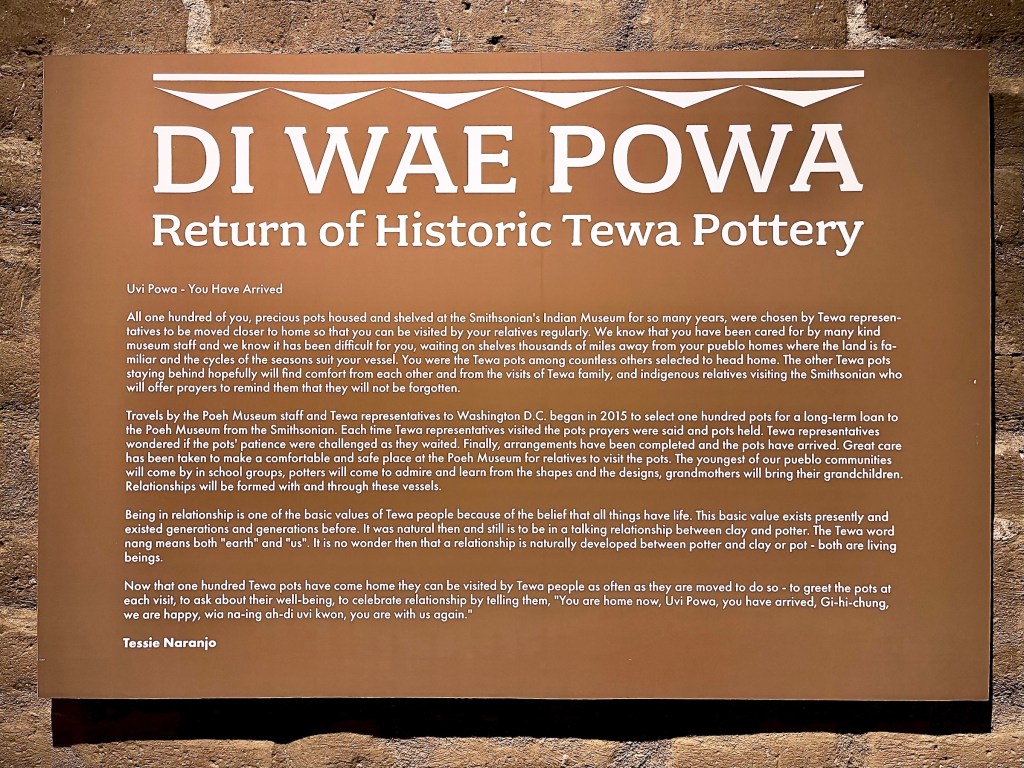

The exhibition is unique as it is the first and, as yet, the only time the NMAI, the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian, released one of their collections into co-stewardship with an unrelated museum. Pueblo elders and governors, museum curators, artisans, and no doubt a gaggle of lawyers, negotiated and prepared for several years to make it happen. Smithsonian conservationists worked with their Poeh Cultural Center counterparts, exchanging practical skills and spiritual cognizance for the well-being of the pots, while developing strategies to allow the ancient vessels to become teachers for future generations of Tewa potters. As far as the Pueblo Peoples of Northern New Mexico are concerned, the clay vessels that now live in the Poeh Cultural Center didn’t just come back; they came home. Here, in their ancestral Tewa Homeland, they were reunited with their loved ones after more than a century of isolation in foreign territory.

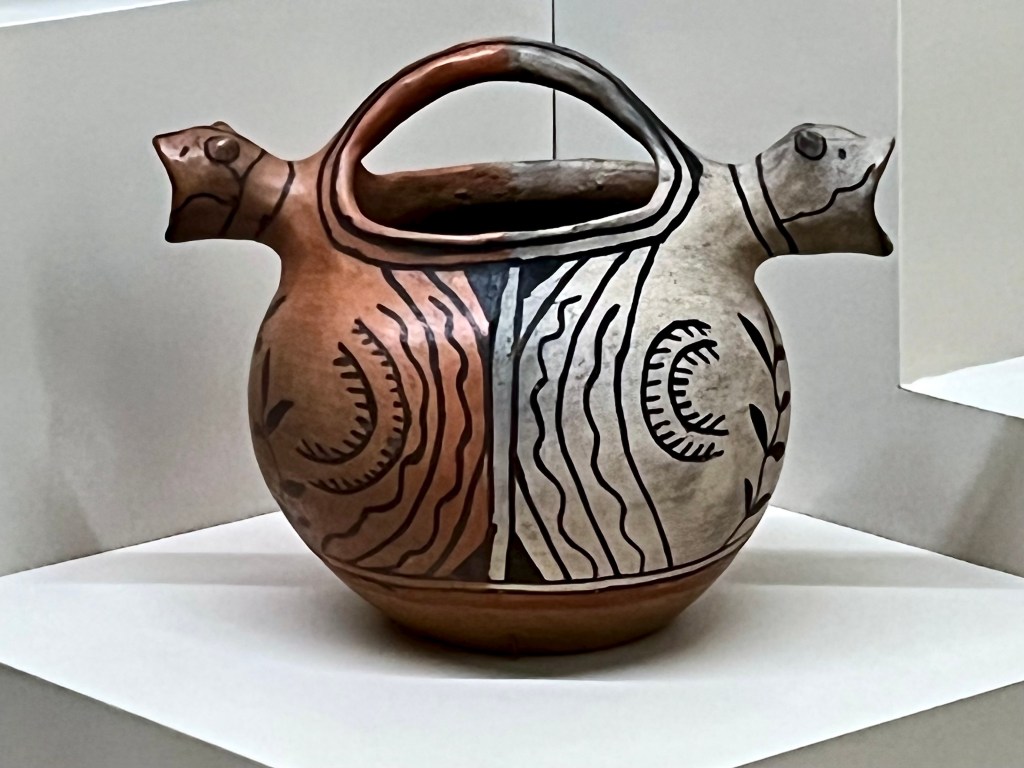

Above: Overview of the 100 returned vessels in their beautiful, specially designed gallery, followed by a few close-ups of selected pots – As far as that was possible considering the reflections of the security plate glass. Generally, there were no individual dates given for the pots, but they were all built before 1930. None of the pottery had been used for ceremonial purposes, nor were they excavated from sacred sites or graves. Equally, none of the pots were signed or could be linked to specific persons or families.

Not the Three Tenors, but a trio of Tesuque rain gods. Toward the late 19th century, rail tourism throughout the American Southwest became ever more popular. To supplement their family income, women in Tesuque Pueblo began to make little seated figurines holding pots to catch the rain, representing rain deities. The ladies sold these souvenirs to tourists at train stations and roadsides, and they became so popular that Tesuque Pueblo mass-produced the little guys until the market collapsed in the early 1930s. I find it intriguing that these rain gods above don’t hold pots, but seem to be encircled by Awanyu, the horned serpent, powerful guardian of water, and bearer of thunderstorms. Awanyu continues to be an important deity in Pueblo mythology, while the rain god appears to be a more playful character. Unfortunately, I found no answer to my query about a connection between the two.

And here we have another intriguing Tesuque rain god figurine. This one is also not holding a pot to catch rain, but is sitting on it as if it were a chamber pot – no disrespect intended! The pot is decorated with zigzag lines, usually representing the presence of Awanyu, or so I understand. The mystery continues …

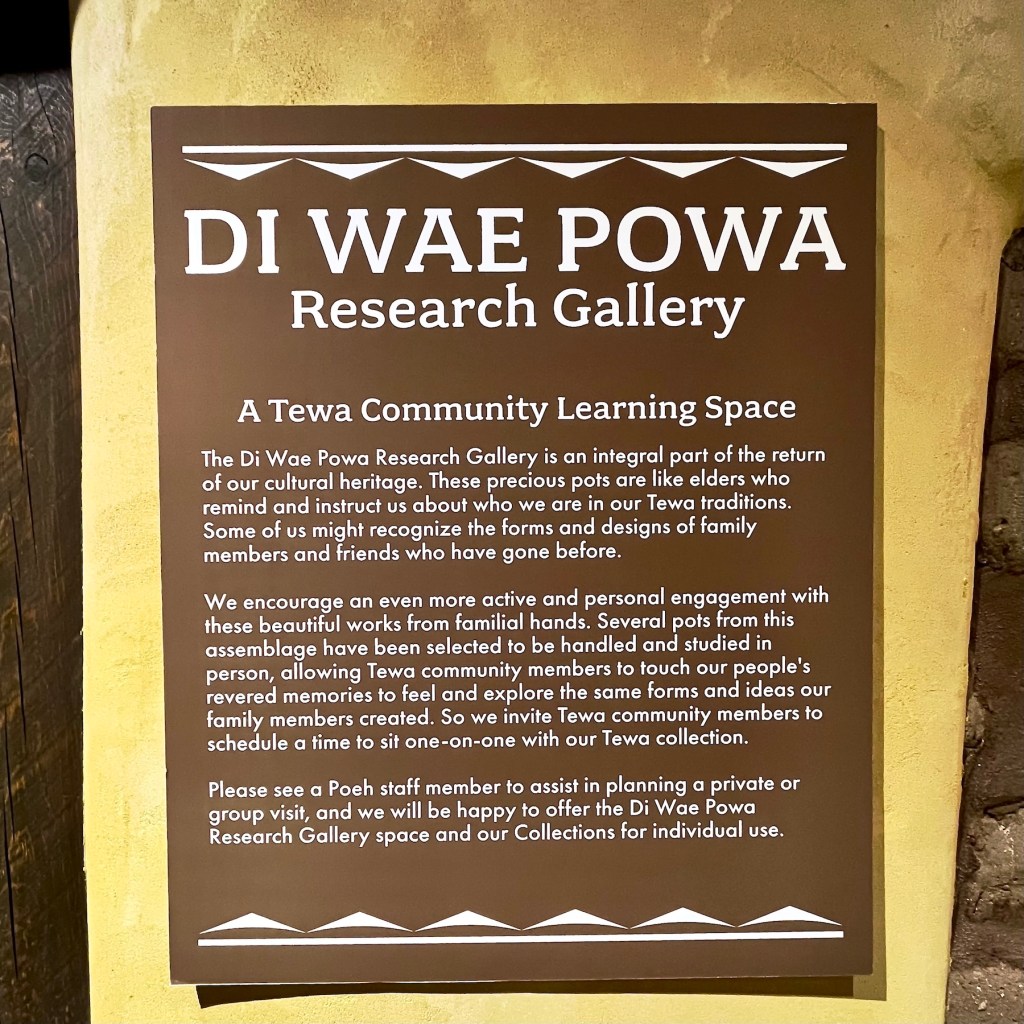

Adjacent to the gallery is the research room, a space designed to facilitate further interaction with Tewa pottery, be that ancient, present, or reaching into the future.

Materials and instructions to begin the learning process.

The ‘Anthropologist George Pepper’ shown in the 1903 photograph on display in the research room is in fact archaeologist George Hubbard Pepper (1873-1924). He was then employed by the American Museum of Natural History and had recently concluded excavations at Pueblo Bonito in Chaco Canyon, NM. If he was purchasing pottery at Pojoaque Pueblo, it was either on behalf of the AMNH or for George Gustav Heye (1874-1957), Pepper’s benefactor, and future founder of the Museum of the American Indian, who, coincidentally, began purchasing Native artifacts in volume in 1903.

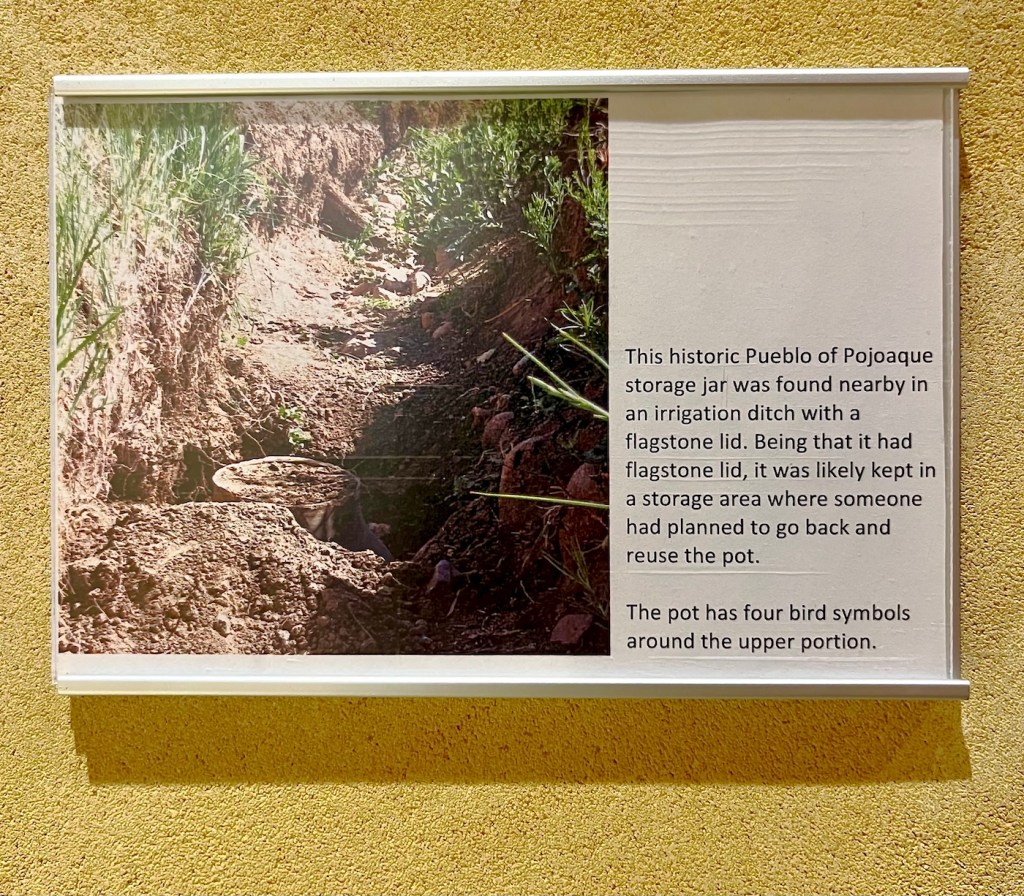

Lastly, a picture of an ancient storage jar that was found in a ditch near the museum, as if it were waiting for its maker to come back for it. Not surprising, really, if we consider that everything moves in circles.

For further enrichment, I recommend the following links:

The Path of a Pot, American Indian, 2019

Di Wae Powa: They Came Back

100 Pieces of Tewa Pottery Returned to Their Ancestral Home in the Rio Grande Valley

Sehr, Sehr gut!!

Dr. Barry N. Leon

707 Cardinal Lane, #A1 Austin, TX 78704

USA

On Sun, Aug 10, 2025 at 5:09 PM NOT IN A STRAIGHT LINE by Photolera

LikeLike