Ravenna, Italy, May 8, 2023

Our balcony view in Ravenna was somewhat industrial, and the viewing of Byzantine mosaics didn’t commence in the best possible way either.

We were docked at a fair distance from town and a shuttle bus dropped us unceremoniously somewhere in central Ravenna, we had no idea where. But I did like some of the advertising.

The deep arcades we saw on the left, reminded me of the typical arcades surrounding the central square of the Bastide towns we have in the southwest of France. As I was taking a closer look, I discovered the delightful façade of a business under the arcade.

It was such an elegant and unique storefront in a great state of preservation. The display in the windows seemed to be about an art exhibition, so we thought it might be a gallery and walked right in.

Inside we had the jaw-dropping vision of more fantastic woodwork. Looking left to right as we entered, we saw a generously sized reception area of … a bank. As the lady who appeared after a slight delay seemed to explain, and which I later confirmed online, this was the main office of La Cassa, a private bank. Not a secret exactly, considering that one can read the name right above the door outside under the arcade 😳 Since we don’t speak Italian, there was no more information available about the wood paneling, nor did the bank’s website provide any clues. According to the historical information, La Cassa moved into these premises in 1905, but the second carved panel outside reads “succ E. Foschini”, which might indicate that the bank succeeded a previous business in this office space. It’s a mystery, and I dearly wish I knew more about the creation and installation of these indubitably Vienna Secession designs.

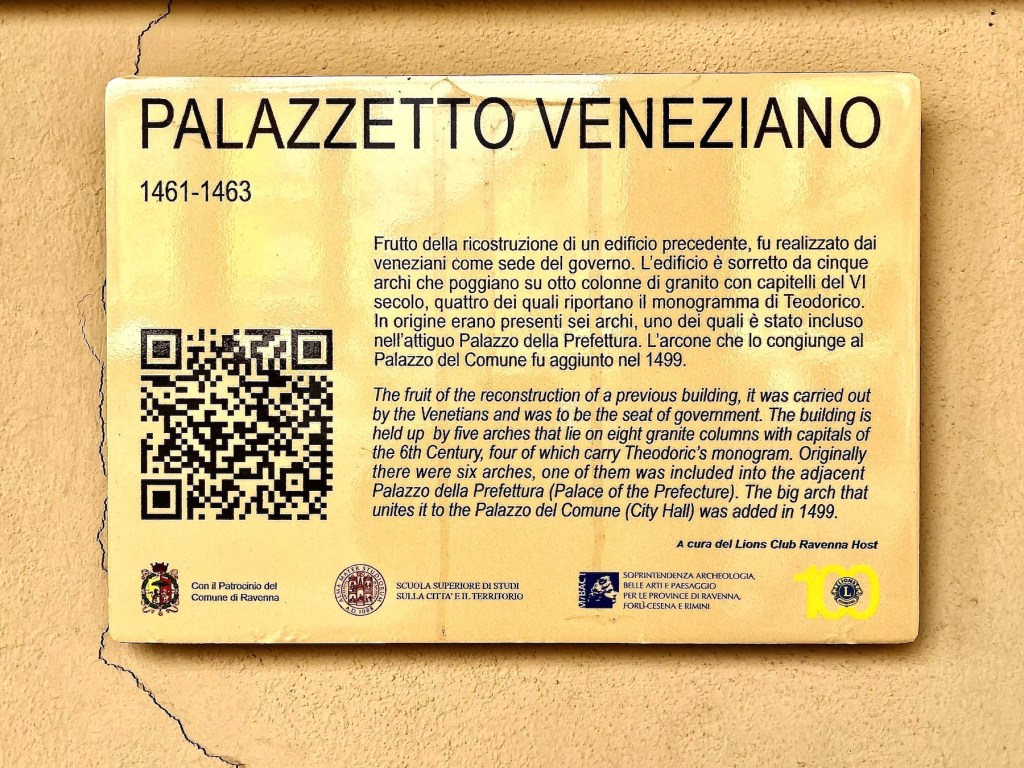

The entire corner of the square was steeped in history. Only later did I realise that the plaques we saw everywhere dispensed valuable information.

But we came to Ravenna for Byzantine Mosaïcs not Art Nouveau, didn’t we? Let’s move on and find some really old stuff.

This church could qualify, I think. It’s the church of San Domenico, consecrated to Santo Domingo de Guzmán 1170-1221, the Castilian founder of the mendicant order of the Friars Preachers, or the Ordo Praedicatorum, otherwise known as Dominican Brothers and Sisters. The Order was confirmed in 1216 by the Holy See. The church was built a half century later, enlarging an earlier medieval church in this location, as was often done. The brickwork of its façade was immensely intriguing, but sadly I couldn’t quite capture its brick-ly aura. I read later that there is a fine collection of Renaissance and Neoclassical Art inside the church, however the building is unsafe and closed to the public.

On the far side of the adjacent piazza, we stumbled across the covered market hall of Ravenna. Compared to most of the buildings in this central district, it is brand-new. But it is located next to the spot where a guild was created in the 10th century to aid and protect the rights of river and lake fishermen. Unionising in the Middle Ages, can you imagine? Their dedicated headquarter, the Casa Matha, had a fish market under its arcades and meeting rooms and offices upstairs. Casa Matha wasn’t demolished till 1893, when bigger and more efficient market premises were needed.

There we were, deep in the historical part of Ravenna and we still hadn’t encountered any mosaics, but at least we were within sight of the compound of the Basilica San Vitale which is also home to the Mausoleum of Galla Placidia, our desired first destination. Both buildings promised to be dripping with Byzantine-style mosaics that were created during the 5th and 6th centuries CE.

Having nearly achieved our destination, we ran into a little snag. When we arrived at the ticket gate, there was indeed a gate, but no tickets. We were told to retrace our steps to the tourism office to purchase tickets there, then return to the gate to have them electronically validated for entry. Naively, we had not been prepared for the volume of tourism in Ravenna even in the off-season.

As a major sponsor of Christian Holy Sites, the Empress Theodora c.500-548, was honoured with a large mosaic panel in the Basilica San Vitale, showing her dressed in imperial robes, crown and jewels befitting her station. The doggy cartoon image above was taken from that panel.

Theodora came from very humble beginnings, and was forced to work as a dancer and prostitute, even as a child. Her marriage in 525 to the then Consul Justinian required the change of a Roman law forbidding high ranking court officials to marry actresses. When Justinian was crowned emperor two years later she became the empress of the Eastern Roman empire and her husband’s chief adviser. Theodora had an illegitimate daughter, whom she openly acknowledged. The imperial couple, though, remained childless. The empress died in Constantinople at about age 48, it is believed that she died of breast cancer. Justinian outlived her by nearly 20 years but never remarried.

The large nimbus of her mosaic portrait indicates that Theodora, who is venerated as a saint in Eastern Orthodox Churches, was a very important personage in the realm.

The life of an elderly tourist isn’t easy. Standing in line in the blazing sun, no seating anywhere. For just a few moments we took refuge in a neighbouring church, …

Finally inside the fenced area, we took our positions in yet another queue that was forming beside the Mausoleum. Here we learned that we were allowed inside the monument for exactly five (5) minutes. FIVE!! After forty-five minutes of running around chasing tickets and standing in line and, more importantly, a lifetime of hearing about the magnificence of Byzantine mosaics, we were granted five minutes to absorb images my father valued among the most beautiful he had ever seen? Tabarnouche, ils sont fous, ces Ravènois !

Having gained entrance to the mausoleum, I was briefly distracted by this beautiful alabaster lined opening, that created such a soft and mysterious atmosphere, before refocusing on our main objective, the mosaics.

The northern lunette above the door to the mausoleum showed one of the universally known representations of Christ as the Good Shepherd. The idea of a pastoral deity as a “good shepherd” usually with a lamb, or a ram, or rarely with a calf draped over his shoulders, was well known throughout Antiquity. Thus the idea was readily adopted into early Christian iconography. Here, we see a young and beardless Christ, posed in the classical Roman manner and draped in purple imperial cloth. He is surrounded by his curiously fluffy-tailed flock, hand-feeding a lamb, while he is holding an imperial staff topped with a cross, identifying him as the ruler over heaven and earth.

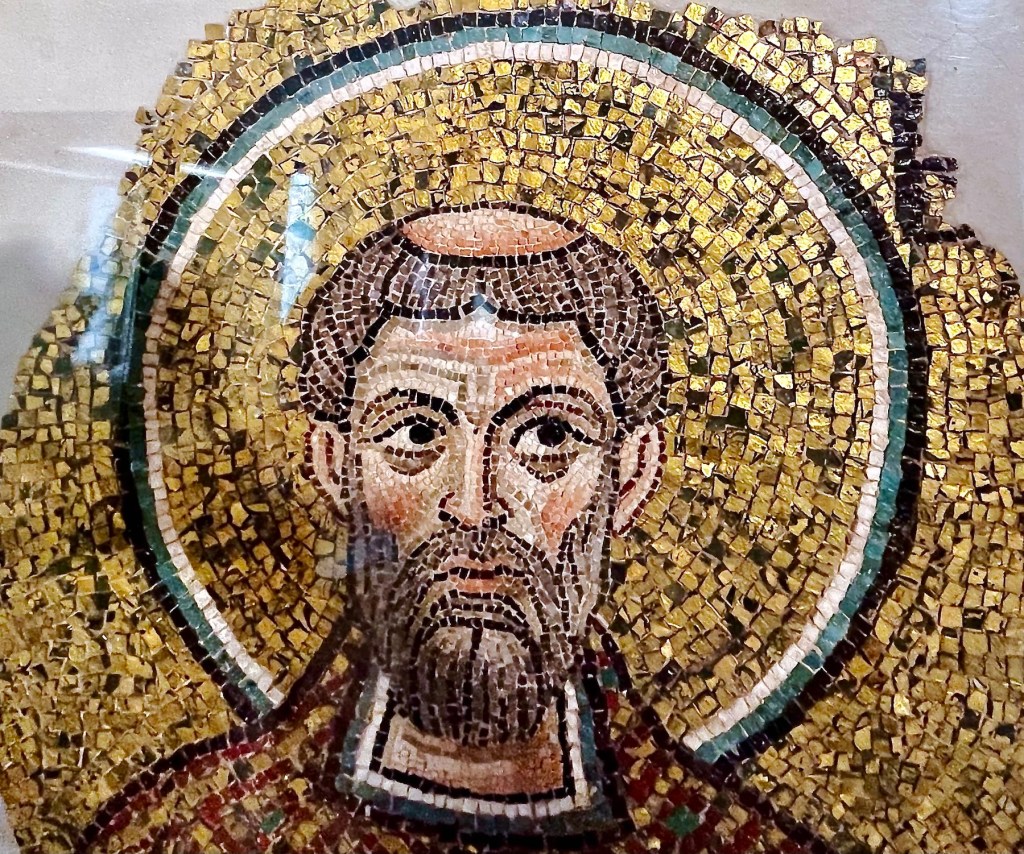

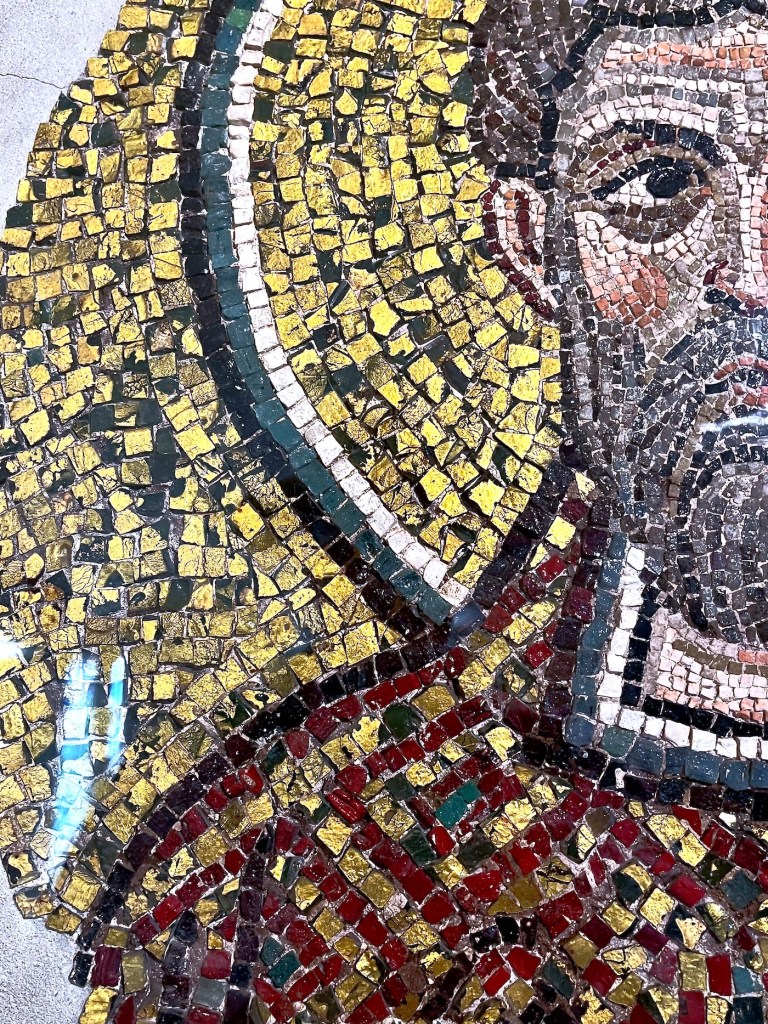

In the enlargement of the decorative border, one can see the tesserae used to create the design. These coloured glass cubes were roughly the size of a fingernail and the artisans, mostly Greeks trained in Byzantium, laid them individually into the substrate. A range of colours with varied intensity was cleverly utilised to show depth or movement. The liberal use of gold added a special dazzle to the most holy characters and scenes. To achieve this, the craftsmen sandwiched gold leaf between thin sheets of clear glass before cutting them into small bits. They often placed an individual gold leaf tessera in a slight angle to better catch the light for a sparkly reflection. That technique worked especially well when the space was illuminated with flickering candle light.

Sadly, we didn’t have any candles illuminating the ceilings, be they flickering or still, so the dimly lit vaulted spaces in my hasty shots are not reflecting the true lustre of these astoundingly well preserved 5th century treasures.

According to the time stamps in my photos, our total time inside the Mausoleum of Galla Placidia was 5″ 40′. One could argue that nearly six minutes inside a small, fairly dark burial chamber is plenty of time to look around and get a feel for the place. Especially in a simple, architecturally undemanding structure, if you only look at dimensions and lay-out.

As was customary, the mausoleum – which was really an oratory – was constructed with reused ancient Roman bricks. It was built in the shape of a cross with barrel vaulted transepts of roughly even length and a shallow dome rising in the centre. The door was in the northern arm, the other three transepts housed sarcophagi, which were rumoured during the Middle Ages to be the finale resting places of Galla Placidia’s second husband Flavius Constantius III, short-term Western Roman Emperor, and their son Placidus Valentinian. It was also said that the empress herself was embalmed in a seated position and placed in the main sarcophagus in her imperial robes. In the 16th century, so the story goes, unruly children accidentally set her remains on fire inside the coffin. Not an image I want to pursue, especially since in all historical likelihood she died in Rome and was buried there.

What made this humble mausoleum so extraordinary to behold were its wall coverings. The floor and walls to a height of about 2 m were clad in marble. Everything else, every square centimetre of wall and ceiling space was covered in mosaic glory. Despite the low lighting, the vivid colours of the figures, symbols, vegetation, animals, and the star-studded sky swirled around vying for my attention, while creating a certain degree of disorientation, especially as the small space was packed with people milling hither and yon. In this chapel of prayer and contemplation, I didn’t have a prayer to absorb the multifaceted imagery in the allotted five minutes, let alone get a feel for the spirit in which it was created, nor appreciate the joy of its execution.

After we were thrown out, I took a picture of the beautifully carved door lintel. Then we crossed the compound toward the Basilica of San Vitale. From the walkway, we had a good view of the Mausoleum’s exterior features.

The layout in a Latin cross with short arms is apparent in the picture, as are a number of the narrow windows. There is a slight dissymmetry in so far as the northern transept appears just a fraction longer than the southern arm, which also has no light opening. The central dome is enclosed in a square tower rising above the gabled transepts and the walls are decorated with blind arcades. Over the centuries, the ground rose around the mausoleum, so it appears a little squat these days.

The basilica across the way, on the other hand, is a rather enormous squat building. The solid deportment of the octagonal structure is reenforced by its flying buttresses. San Vitale is one of only a handful of surviving examples of the Imperial Roman custom of using this lateral support system for domed structures which, by the end of the millennium, became a popular choice among builders of Gothic cathedrals across Europe and beyond.

And speaking of domes, there is another Imperial Roman invention that was used in the construction of both the mausoleum and the basilica, as well as any number of other buildings in the Roman territories. It is the technique of constructing vaulted ceilings and domes with hollow terracotta tubes, a technique which may have originated with craftsmen in Roman North Africa. At the height of their use, the tubes were roughly 20 cm/8 inches long with one end narrowing to a nozzle.

[There are two pictures at the end of the above linked article to show a prototype]

These lightweight tubes could easily be mass-produced by local potters. For a vaulted ceiling, like we saw over the four transepts of the mausoleum, the hollow tubes were interconnected by inserting the nozzle into the wide end of the next tube. Several connected tubes could be arched toward the centre of the transept, where they met tubes advancing from the opposite side – imagine it like two swimming pool noodles curving toward each other. The two half-arches were then joined with a central tube with two wide ends to receive the right and left nozzles, acting like the keystone in a brick arch. Any number of these semicircular arches could be quickly assembled and lined up next to each other to become a vaulted ceiling, secured by mortar, of course.

To create a domed shape, the terracotta tubes were joined to form either rings of decreasing circumference or spirals. In the Basilica, the terracotta pieces in the shape of amphorae were laid in a continuous spiral. But with a dome diameter of 18 m/59 ft, that was really pushing it, because the diameter of the dome was the most critical limiting factor for this lightweight type of construction without auxiliary support.

The construction of San Vitale began in 525 CE under the rule of the Ostrogoth king of Italy Theodoric (493-526). After his death, the construction continued under the auspices of the Eastern Roman Emperor Justinian the Great and his consort Theodora, and the church was consecrated in 547 CE by bishop Maximian.

Stepping inside the basilica, the grandiose dimensions and the fantastic decorations were simply mind boggling.

Floor mosaics were generally not made of glass but of marble, glazed ceramic shards, granite, and other rocky bits and pieces.

The central dome of the basilica had been re-decorated with baroque frescoes and other 18th century design elements which I didn’t like at all.

After the crowded spaces in both the mausoleum and the basilica, we found some soothing solitude among the forgotten herbs of the Rasponi Garden, il Giardino Rasponi o delle Erbe dimenticate. This tranquil spot in the shadow of the Ravenna cathedral used to be part of the gardens surrounding the 15th century Palazzo Rasponi Murat, commissioned in 1400 by Giovanni Balbi. Camillo Morigia, the famed architect who built the Dante Alighieri Tomb, designed the gardens in 1780. What remains of the former estate apart from the palazzo itself, which is one of the oldest buildings in Ravenna, includes a lovingly restored apothecary garden replanted with many of the original 18th century Mediterranean and lesser known herbs aka erbe dimenticate, forgotten herbs. The tiny café on the premises serves the locals – and the occasional tourists like us – with homemade, organic backed goods, fresh juices, and honey.

Since we began our Mosaïc Journey through Ravenna in a mausoleum, it seemed fitting to conclude it in a baptistry, namely il Battistero degli Ortodossi o Neoniano, the Orthodox or Neonian Baptistry right next to the Cathedral of the Resurrection of Jesus Christ and the museum in the archbishop’s palace, that we visited in conjunction with the baptistry.

In the Neonian Baptistry, we had to limit our visit to five minutes again, although it wasn’t crowded at all. But at least nobody yelled at me like the overburdened guardian of the mausoleum did.

The Neonian Baptistery is the oldest of the extant monuments of Roman Antiquity in Ravenna, as construction began during the reign of Roman Emperor Theodosius the Great, Galla Placidia’s father, the last emperor in charge of the entire Roman Empire before it was permanently split in West and East domaines.

The baptistry was commissioned by Bishop Ursus during the mid to late 4th century and for simplicity’s sake it was erected over a former Roman bath. Some decades later, the structure was renovated, and marble, stucco, and Byzantine-style mosaics were added to finish the interior as per instructions of Bishop Neonis, hence the name.

In Early Christianity, baptistries were commonly built as octagons, representing the seven days of the week plus the Judgment Day. However, the Neonian Baptistry is a singular monument as it is the only known baptistry of its period to have survived nearly intact, both structurally as well as in the superb condition of its original interior decorations.

Against a blue background, the twelve apostles dressed in priestly garments carry laurel wraths, a symbol of triumph. Five apostles walk clockwise, lining up behind St. Peter, while the remaining five follow St. Paul in a counterclockwise procession. The apostles surround the central medallion in the baptistry celebrating the Baptism of Christ.

In the museum next door to the Neonian Baptistry, we had a somewhat unusual experience. As we entered the building a member of staff kindly asked me, if I wanted to use the elevator. An offer I gladly excepted. Following her directions, we first crossed the ground floor to a rear exit for staff only which led to an enclosed garden with some parking at the far end. As we were trying to find the elevator, several priests crossed from the parking lot toward the museum. Every one of them told us to get out, some in no uncertain terms. I wouldn’t have imagined that an old woman with a walking stick crossing some institutional green space could provoke such a strong negative reaction in men of God. It gave me a more intimate understanding of the Inquisition.

We had a good time in the museum, home to a number of intriguing artefacts, but there were no more photo opportunities.

After our museum visit, it was time to find our shuttle bus and return to the ship for my cooking lesson.

This time we learned how to prepare a Venetian staple, Baccalà Mantecato, creamed cod (not pictured), and another typical Venetian antipasto, Sarde in Saor, fried sardines in a sweet and sour marinate.

When our fishmonger back home had fresh sardines, I repeated the recipe and it came out great. I served it as a main dish with polenta, though.

Back aboard ship,

after my cooking class, our Team Trivia session, and cocktails, we enjoyed one last fabulous lobster meal at the lovely Silver Note restaurant with its funky volcanic dishes.

During the night, we crossed the Adriatic Sea one more time to reach Trieste at “the top” of the Dalmatian coast.

Trieste, Italy, May 9, 2023

By 07h30 Captain Georgiev, Master of the Silver Moon, manoeuvred her ever so gingerly toward the cruise pier of the Trieste harbour.

It looked like we would be very safe during our stay in Trieste, because we were docking right alongside the Maritime Border Police devision of the Italian State Police.

If you click on the left picture above to enlarge it, and look very carefully, you might see a small, dark triangle rising above the karst cliffs in the centre of the picture. That is the Temple of Monte Grisa, officially the National Shrine of Mary Mother and Queen or Santuario Nazionale a Maria Madre e Regina which we saw close up later during our bus tour of Trieste.

In the same picture, and even more obscure than the church on the ridge, you may detect a vaguely white rectangular dot at the end of the dark promontory at sea level, just above the stern of the little ship. That is the rather splendid Castello di Miramare. It was built for the Austrian Archduke Ferdinand Maximilian, who, through a thoroughly imprudent stratagem by French Emperor Napoleon III, became the puppet Emperor Maximilian I of Mexico in 1864. A mere three years, two months and nine days of utter upheaval later, the first and last Maximilian of Mexico was executed by orders of the legitimately elected president of Mexico, Benito Pablo Juárez García, whereupon Maximilian’s wife, the Empress Carlota lost her mind.

As romantic as that sounds, I made it up. The empress had traveled to Europe well before her husband’s violent demise*. Carlota, born Charlotte Princess of Belgium, was on a desperate mission to reverse the French emperor’s betrayal of their regime in Mexico. She failed in her attempt, as well as in trying to enlist the pope’s support. As a result, she became increasingly despondent, escalating into episodes of paranoia, so that she was placed under guard in Castello di Miramare. At this point, she still didn’t know of her widowhood. It was assumed that she was deliberately poisoned with anionic bromide back in Mexico, a neurotoxin which can accumulate in the system and cause severe psychosis. For the ex-empress it meant madness from which she never recovered.

I knew of that sad history before we cruised around Trieste, but I had never heard of Castello di Miramare, which is, judging by photos on the internet, a stunning building. Our guide told us stories about the castle, the beautiful gardens and its unfortunate owners, but we never got close enough to actually see the estate.

* Edouard Manet painted a famous series of pictures on the subject.

After a fairly boring and rainy tour, guided by a very knowledgeable albeit rather sarcastic guide who plainly felt superior to us Anglo-Saxon tourists, we arrived at the before mentioned National Shrine of Mary Mother and Queen which was established by Bishop Antonio Santin. In 1959 he obtained permission from Pope John XXIII to build a pilgrimage centre on the cliffs 300 m above the sea and his beloved Trieste.

Currently, the building serves the Regional Council of Friuli-Venezia Giulia [not affiliated with the City of Venice! The name of this autonomous administrative region within the Republic of Italy goes back to the imperial Roman Regio X Venetia et Histria, founded by Emperor Augustus in 7 CE]

After some further perambulations, we returned to the Palazzo Stratti for refreshments. The Caffè Degli Specchi, Café of Mirrors, has operated here since the building was finished in 1839. It’s the only one left of four cafés in this grand piazza.

Since it was lunchtime, the terrace was crowded and the service seemed slow – mostly because we were very, very thirsty and it was hard to be patient. We didn’t want a whole meal, just something to drink and a little snack. My husband ordered an over-the-top ice cream creation with loads of whipped cream, very Viennese, while I thought I ordered a little something to nibble with my glass of local Prosecco. Think again! I got a beautifully arranged platter of smoked hams, mascarpone, capers, crusty brioche, and, and, and. I even asked our waiter if there was a mistake, but he confirmed that it was my order. The sun had come out and this interlude on the café terrace was hugely enjoyable, especially combined with the entertainment of people watching, not to mention the outrageous antics of the pigeons.

That was it, our Mediterranean Cruise on the Silver Moon was over. While sailing from Trieste to Venice through the dark of night, our large suitcases were collected by the crew at midnight, whereas we had to be ready to disembark with our carry-ons the next morning at 08hrs sharp. From the cruise and ferry terminal in Fusina on the mainland, we were bused to the Island of Venice and released into the world at large.